The Literary Past: Little Women Part Two

The Reality that Shaped Louisa May Alcott and Her Fiction

It’s 1868, and a heavy curtain of pollution hangs over the cobblestone streets of Massachusetts; the clatter of printing presses carries from busy town centers, and in meeting halls, voices sharpen over the future of the republic. The war is over, but the promise it held for women has been cut short.

For years, they’d marched beside abolitionists, spoken from pulpits, taught in freedmen’s schools, run farms and businesses, staffed hospitals, and organized massive relief efforts — holding the country together while its men fought. The newly ratified 14th Amendment grants citizenship to formerly enslaved men, but in Section 2, it also marks the first time the Constitution uses the word “male” in connection with voting rights. One sex will hold full rights. The other will not. All enslaved people are now free, yet women, Black and white alike, are still denied the ballot.

For women like Louisa May Alcott and her mother, Abigail, it is more than a political slight. It is the dismissal of years of labor and sacrifice. Louisa has returned from nursing in Washington, where the stench of gangrene and overcrowded wards clung to her clothes. Abigail has stayed home in Concord, her days filled with organizing aid drives, chairing meetings, and speaking for women’s rights.

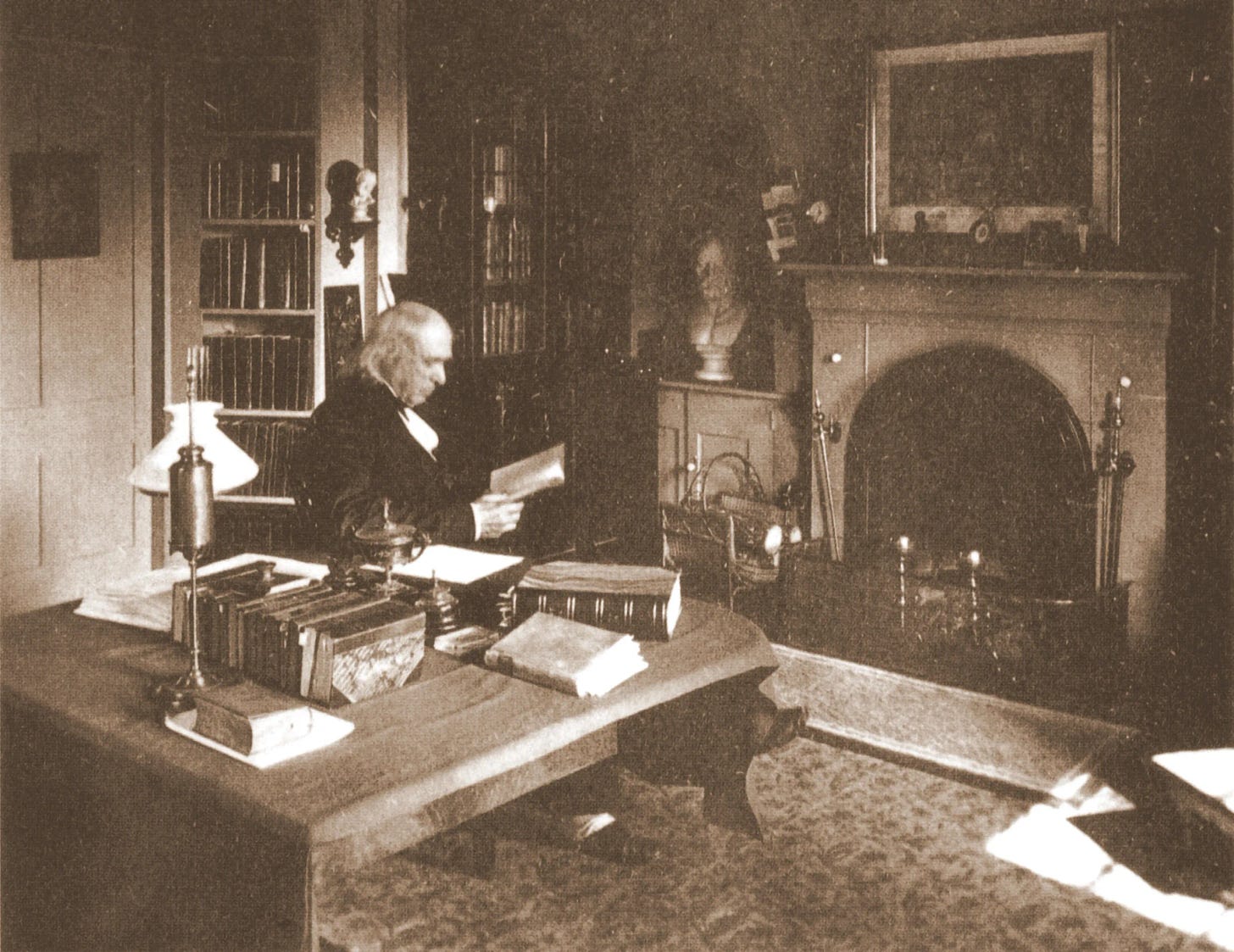

For the Alcott women, wartime labor and activism weren’t abstract ideals — they were the work that kept the family afloat. Bronson Alcott, the family’s philosophical patriarch, has vision but little talent for earning a living. The practical burden falls to the women, who juggle public service, creative work, and the constant effort of keeping food on the table.

And all of this plays out against the backdrop of Concord. A place where Ralph Waldo Emerson’s voice might drift from a lecture hall, where Henry David Thoreau’s ideas on self-reliance still hang in the air, and where the Alcotts’ own parlor plays host to reformers and thinkers intent on reshaping society.

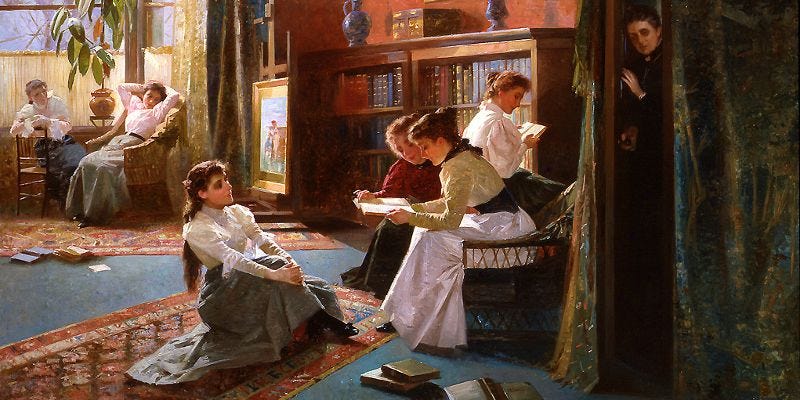

That same year, Little Women appeared in print. In Massachusetts, girls are reading more than ever. The state boasts one of the highest female literacy rates in the nation, and those young readers are ready for more than moral lessons. They want to see themselves on the page. Alcott’s characters give them that: women making choices, wrestling with ambition, and imagining a life beyond the boundaries set for them.

Opportunities for women are beginning to shift. The sewing machine turns domestic labor into speed, and sometimes, profit. The typewriter, still rare, suggests an entirely new professional landscape. Even these modest advances expand the horizon of what’s possible.

Alcott’s brilliance lies in refusing to discard the traditional ideals of womanhood, but instead bending them toward power. In her words, sewing for soldiers, teaching children, and visiting the poor are not passive acts. They are civic ones. To put it simply, the home isn't a cage; it's a headquarters.

This was the Massachusetts Louisa knew: noisy, divided, changing fast, yet clinging to tradition. And it’s from this exact intersection of chaos and possibility that Little Women was born.